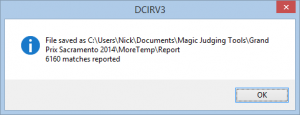

This is the final collation of Grand Prix – Sacramento matches for submission to Wizards of the Coast. A total of 6160 matches were played over the course of this tournament, each of which has to be entered into the system. OK, we’re talking two days, 10-12 hours each. Not so bad, right? Let’s drill deeper.

This is round 3 of Grand Prix – Washington DC. Not all hours, or minutes, are created equal. Let’s cut to the chase. Generally, the bulk of result entry happens in a wave about 20-25 minutes long, starting from about 15-20 minutes remaining in the round, depending on the specific tournament size and format. So, let’s say roughly 600 results in 20 minutes, or 30 per minute, or one every two seconds.

Every scorekeeper that I know enters what I call the trance when they get to this point in the round. You probably recognize it if you think about it. That moment where you stand in front of them to ask some question and it doesn’t really seem like they register that you’re there, or when they look disturbed if you really try and get their attention.

Nothing that’s being done during this time is particularly complicated – it’s just that it’s being done a lot, over, and over, and over again.

If you had to sit down and think in your conscious brain about each of these events, it’d just take too long. Just like with muscle memory for musicians, the way that you handle this is by having your brain recognize some basic patterns and falling into an instinctual rhythm. Your brain helps you process some of the data without you having to stop and really think about it, kind of like you never think about breathing, or how to swallow.

Blah blah blah, armchair psychobabble, right. Here’s all that actually matters: Anything that disrupts the trance rhythm is disproportionately expensive to efficiency. Different scorekeepers will handle this with differing levels of effectiveness – some will merely be thrown off their a lot, whereas others will be thrown off dramatically so. Regardless, though, there is a hidden cost to any such disruptions – not only the time to address the disruption, but the cost in time to get yourself back into the flow of things.

In practice, this means that effort put toward preventing unnecessary disruptions and lapses in consistency will have an outsized effect on the ability to get a round turned. Let’s look at some concrete examples.

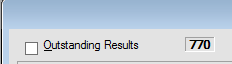

Turning upside-slips around, or unfolding crumpled slips? Brutal. Informal, back of envelope measurement suggests that a single unexpected upside-down slip in a pile will cost you a full four slips worth of processing time. People who’ve worked with me will note that even though TOs keep getting more professional and have become more and more prone to bringing a fancy plastic tub for result slips, I continue to cannibalize an empty booster box for this purpose. Why? Because it’s closer to the size of a result slip and doesn’t result in as messy of a giant pile of skewed slips. Players? Take the time to make your slip go in the box nicely and face the same way as the slip before yours. Judges? One of the most impactful things you can do if you’re around the stage (much more so than outstanding table handling, generally – more on that in the future) is to get all the slips into a single pile facing the same direction, though if you’re going to do this, you have to do it right. A recent epidemic has been judges who do this quickly and miss a few slips here and there. No big deal, right? Well … not so much …

Don’t be that judge that takes the next small batch of slips, gets them into a pile, then stands there and holds them out at the scorekeeper and refuses to do anything else until they acknowledge you and take the pile. You’re costing a lot of time by breaking their trance over and over again. Just keep collecting slips, they’ll take them when they’re ready.

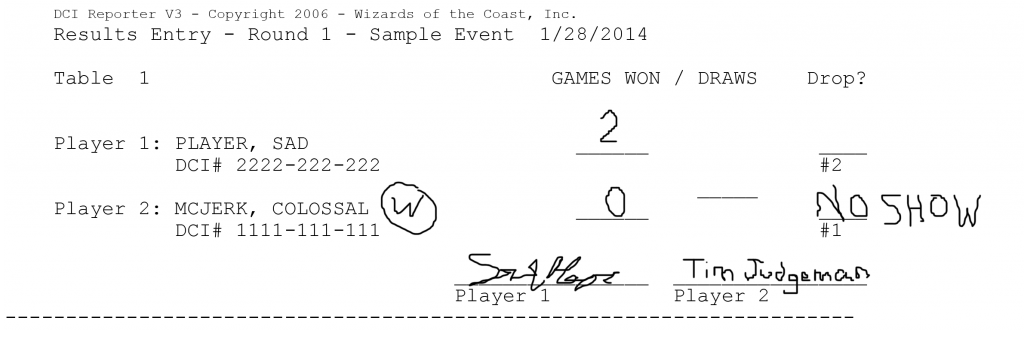

Don’t be that player that makes a mess on your result slip because you write life totals on it, or because you’re careless and then have to scribble out a typo, or because you feel like drawing smiley faces and writing “No” under the Drop column because you’re so happy that you won. Anything other than game scores and signatures is, in and of itself, a disruption. A necessary disruption, in the case that we need to slow down and parse a drop, or a penalty, or a name correction. But when those stray marks are there for no good reason at all, it slows things down far more than you realize.

There are many more such examples, which I’ll get to when I start codifying things into practical advice. For now, though, just understand – there’s a rhythm to data entry. If you disrupt it, especially if it was for no reason at all besides carelessness, you shouldn’t wonder why I’m so grumpy.