At dinner on Saturday at Grand Prix – Phoenix, a few of the older and more seasoned judges were doing some informal debriefing (read: ranting) and at some point, I was referring to the critical path and was a bit surprised to hear that this wasn’t a universally understood concept.

Pervasive in the software and business world, the critical path is, in brief, is a project management concept that identifies the longest chain of dependencies of a project that must be completed to finish the project, which then dictates the fastest that the project can possibly be completed. This is important for two reasons. First, any delay to tasks that are on this critical path delays the completion of the entire project (as opposed to delays in other areas, which are absorbed by the length of the critical path, at least until you delay them so long that they take over as the new critical path). Secondly, and more positively, finding ways to save time on the critical path will concretely speed up completion of the whole project.

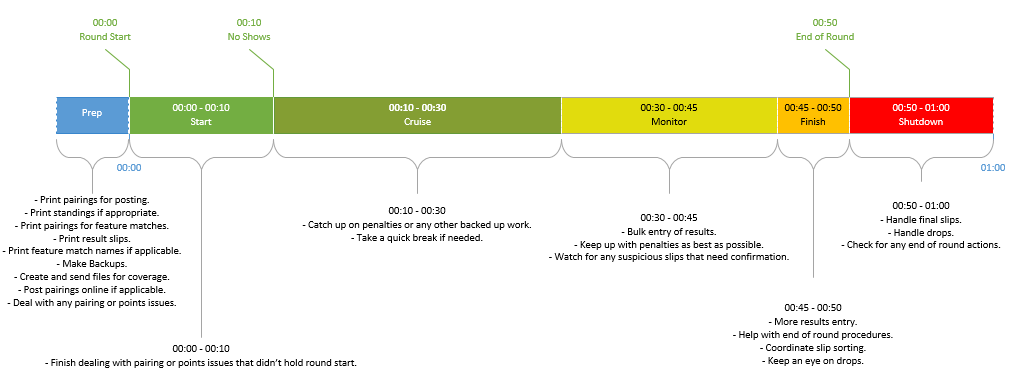

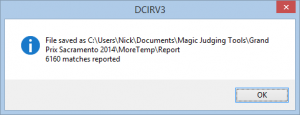

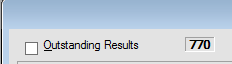

At the end of the day, a tournament is actually just a large-scale project that needs to be completed, and it possesses a critical path like any other project. Dealing with bye and registration issues so the tournament can start. Printing and posting pairings. Collecting the last results and handling drops.

This isn’t actually a novel concept – I’ve talked about it at length under several different guises. However, there are some benefits to thinking about it specifically in the project management sense.

Everyone in the tournament – players, judges, staff – has the potential of being on the critical path, depending on how things go. But there are roles that are more or less likely to end up on it at various times. Any individual player, for example, is relatively unlikely to (unless you play incredibly slowly – we saw at least 0-0-1 result today, ick!). And some are obviously on it all the time – you do know what you signed up for, right scorekeepers?

For most judges and staff, though, your jobs will intersect with the critical path intermittently. One of three things will generally be true:

1) You’re obviously and currently on the critical path. If you’re the guy managing the drop list at the end of the round, and you’re still handling players trying to drop after the last slip has come in, you’re it. The tournament speeds up or slows down based on what you do. It’s important to understand the impact that you have here. At your average, say, 1500 player tournament, every second that you dally costs thirty minutes of person-time. Think about that for a second – it takes you under a minute of wasted time to eat a full day’s worth of time. And it works the same the other way, as you do things faster.

The moral of the story here is – whatever you’re doing … do it faster. Do it better. Find a way to be more efficient. If you’re sauntering, if you’re chatting, if you’re confused, you’re doing it wrong. Run (or, if you subscribe to the never run school of thought, power walk). Tell people you’ll get back to them later. As someone that believes that getting done faster is the top goal, few things irk me as much as someone on the critical path not realizing that they are, or not acting accordingly, and those of my ilk will ride you relentlessly when this happens. It’s nothing personal, you’re on the critical path.

(Side note for judges: some people are temperamentally suited for this sort of thing better than others. If you’re not, think about the sorts of roles that you might want to seek out or avoid, but it’s absolutely a skill that you’ll want to work on as you advance your career, since there’s only so far you can go avoiding it.)

2) You’re not on the critical path, but you could become so if you do what you’re doing wrong. You’re giving a ruling during the middle of a round and it starts to drag. Turns into an investigation. You can’t quite decide how to rule. Suddenly, you’ve just given a 15 minute time extension. If you’re lucky, it’s two aggro decks and they finish early anyway. But maybe they’re not, and not suddenly that’s the last match of the round and everyone’s waiting. You just caused a critical path shift and slowed the tournament down.

In this case (which is the usual case), there’s less obvious and urgent need to do what you’re doing faster right now, since a normal pace of progress will probably just be absorbed into the current critical path. Just make sure you’re keeping a sense of how things are going, how much time you’re taking, and whether you’re at any risk of becoming that long pole. Part of the art of judging is understanding when you’re coming up against that line and scaling your expediency accordingly.

3) What you’re doing has no risk of ever being on the critical path. It is true that there are some selected activities that work this way – we’re going to check as many decklists as we have time for and then move on – that are valuable in a timeboxed sense and help provide better tournament integrity and customer service. Unless you’re doing one of these things, though, if you’re in this situation, you should probably think about whether what you’re doing is even valuable enough to be doing or whether you should be finding more impactful activities. Something that the tournament wouldn’t wait on oftentimes is something the tournament doesn’t even need.

This isn’t meant to be all doom and gloom and telling you to work harder. Effective critical path recognition and management can help you to make better decisions in the other way as well. If you’re hovering around the stage waiting for something to do while the last three matches are playing, you’re just standing around tensed up for no reason. Relax, sit down, take care of your ailing legs. You’re not critical path right now and you can’t do anything to speed the tournament up.

I’ve said it before and probably will many more times. Get done faster. But put some thought into doing it smarter – at the right times and with the right urgency – as well.